One of Marlboro’s most important influences was the revered violinist Felix Galimir, who for 45 years, from 1954 through 1999, shared a deep musicality and infectious personality with generations of eager young participants. In so many ways, he opened new worlds, not only in terms of the repertoire for which he became known but also in the thoroughness and care with which he explored each piece.

An adherent of the Second Viennese School closely associated with Alban Berg, he led the Galimir String Quartet with his three sisters while still a teenager. In 1936, the Quartet won the Grand Prix du Disque for their recordings of the Berg Lyric Suite as well as for one of the first recordings of the Ravel Quartet, with both composers coaching and attending the recording sessions. It was this diverse background and knowledge that Galimir brought to Marlboro, having fled Vienna for Palestine and coming to the U.S. in 1938.

Galimir’s knowledge of the string repertoire and his experience as a violin and chamber music coach at Juilliard, Curtis, and Mannes made him an invaluable colleague of Rudolf Serkin. In annual auditions, in selecting works and personnel for pieces suggested by the participating artists, and in proposing senior artists to be invited to join the Marlboro family, Galimir played a key role in the development of three generations of musical leaders who were deeply influenced by their summers in Vermont.

He introduced string players, many of whom went on to form prominent string quartets, to the worlds of Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern while attempting to convey these composers’ deeply expressive qualities, which he felt were not sufficiently recognized. For those fortunate to have participated in or heard his conception of Schoenberg’s Verklaerte Nacht, it remains a most treasured performance, and his Pierrot Lunaire was a revelation for the artists who had the life-changing experience of playing it with him.

Another coveted Marlboro experience for any young string player was to play one of the Bartók string quartets with Galimir in the second violin chair. But, then, all Galimir performances had a rare and distinctive quality—Haydn, Mozart, Dvořák—offered a special musicality and a sense that much more had been discovered and mastered than just the notes in the score.

A dynamic personality, Galimir was both demanding and inspiring. He had a wry sense of humor and a twinkle in his eye, but he also had a most expressive way of displaying his unhappiness when his colleagues were not properly prepared or focused. He was definitely of the opinion that the composer deserved the utmost respect. He cared about young musicians on a human as well as a professional basis with the same fervor that he had for music, and for so many in the Marlboro community, he was a beloved father and uncle figure as well as an inspirational mentor and friend.

As the New York Times wrote upon his death:

“It would be difficult to overstate Mr. Galimir’s centrality in American chamber music life but perhaps the best measure of his influence is that at virtually any chamber music concert today, at least one musician on the stage is likely to have studied with, been coached by or performed in an ensemble with him.”

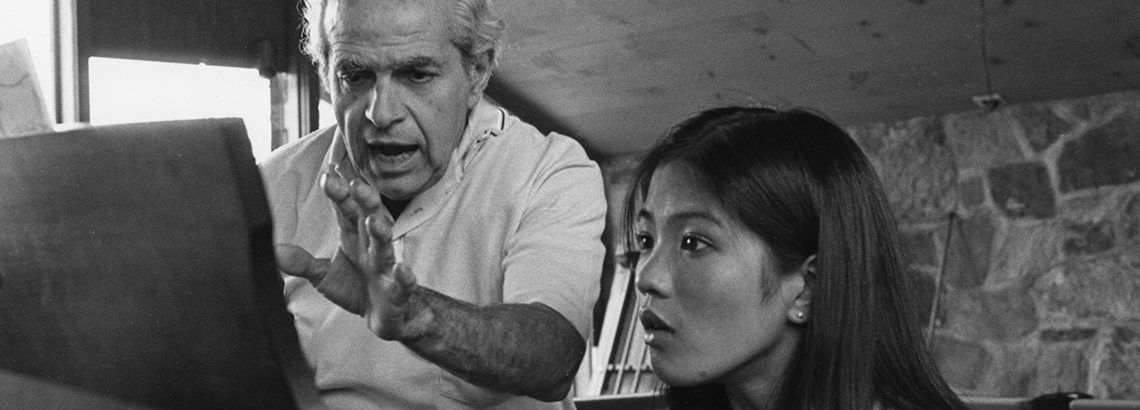

!["What was very interesting was, without explaining, he would play like a Gypsy violinist. He played with enormous emotion, and that is what I love in the Second Viennese School. There is so much emotion, all, it’s bubbling underneath, and even in Webern, whose music is regarded as mathematical and so precise… [Galimir] cared about the Second Viennese school so much, and so do I, and for him it was something that he championed in his youth already. And he cared about it all his life, and that is something wonderful and that carries." Mitsuko Uchida | Pictured with Peter Seidenberg, Mitsuko Uchida, Mary Nessinger, Marina Piccinini, and Todd Palmer rehearsing <i>Pierrot Lunaire</i>. Photo by Pete Checchia.](https://www.marlboromusic.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/AH-122-173x133.jpg)

!["I have a feeling with Madeline [Foley] that almost she and Felix, almost more than anyone, were the two people who Serkin perhaps felt they gave this sort of absolutely solid and exacting kind of musical instruction that he himself would want to give… With Felix and Madeline, you had the feeling that this was absolutely of a pace with the deepest things in their lives, and, in a way, I feel that they were people who almost taught us most when it came down to working on what these pieces were all about and the different styles." Richard Goode | Pictured in a light moment with a tour group including David Golub, John Graham, James Kreger, and Miriam Fried, joined by Endel Kalam on Miriam Fried's lap, Madeline Foley, Luis Batlle, and Rudolf Serkin.](https://www.marlboromusic.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/wmf-173x133.jpg)